ch. 5, a long form book response to Disarming Scripture by Derek Flood

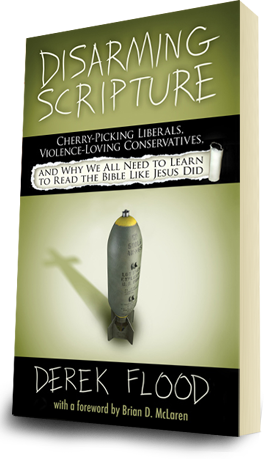

Derek Flood has written an excellent book explaining the issues I covered in my blog series this past autumn. My series is titled "Not everything Biblical is Christian." His book is titled Disarming Scripture. Cherry-picking liberals, violence-loving conservatives, and why we all need to learn to read the Bible like Jesus did. It is certainly a mouthful, but his examples are better than mine and deserve a thorough treatment here. Flood's book is ten chapters long and I intend to speak about each chapter in separate blog posts. I heartily recommend this book for the thinking Christian.

Chapter 5 is titled, "Facing our darkness." Based on his previous chapter, in which he discusses ethics as necessary for Biblical exegesis, he supplements the earlier idea of faithful questioning: faithful questioning motivated by compassion. p. 91 More than any of the previous chapters Flood shows multiple examples from within the Old Testament in addition to inter-Testament questioning.

The problem of evil is a topic of dispute between the authors of the Bible. Unfortunately, one has to go to the old King James translation to get a literal translation of the Hebrew word ra'.

Amos 3:6 Shall a trumpet be blown in the city, and the people not be afraid? shall there be evil (ra') in a city, and the Lord hath not done it?

Isaiah 45:7 I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil (ra') : I the Lord do all these things.

1 Kings 22:23 Now therefore, behold, the Lord hath put a lying spirit in the mouth of all these thy prophets, and the Lord hath spoken evil (ra') concerning thee.

The question is, was God really responsible for these evil things, especially if God is perfectly revealed in Jesus? The Old Testament is full of ascriptions of sickness and defeat to God's judgment. But when Jesus encounters sickness, say a blind man, his disciples want to know whose sin caused it, but Jesus counters neither. Jesus combats sickness and death because they are the work of the demonic, not God. Jesus' move is not unique. Flood notes that a book between the Testaments, Jubilees reframes things attributed to God in the Old Testament and attributes them to the prince of demons. See a short summary of this at Wikipedia. One notorious Bible contradiction serves as an example of Jewish theological development; who motivated David's census. In the earlier account of 2 Samuel 24:1, God did. In the later retelling at 1 Chronicles 21:1, Satan did. Jesus' approach to the world is akin to the later theology of the Chronicler. Evil spirits cause bad things and bad things happen for no reason but God is not the problem but the solution to those bad things.

In the Old Testament, the Babylonian prophet, Ezekiel is a source of a few examples of faithful questioning.

In Deuteronomy 28:63 God is said to be pleased to ruin and destroy his people if they are unfaithful. But Ezekiel 33:11 says God takes no pleasure in the death of the wicked.

In Deut. 5:9 and Exodus 20:5 God punishes the multiple generations for the sin of the fathers, see my post here, but Ezek. 18:19-20 God only punishes the sinner and not the sinner's descendants.

The question is, did God change his mind or did his prophets change their theology in response to faithful questioning with compassion? I used to believe the former, it is simpler when one is committed to an inerrant Bible. As Flood sees it, these contradictions are not mistakes for Bible critics to harp on, but "intentional contradictions, a record of the dispute found throughout the Hebrew canon, cataloging developing and conflicting views of God. Therefore, rather than viewing such contradictions as something embarrassing we need to explain away, we can instead view them positively as a record of moral development that emerges through dispute and protest." p. 98

For me, this is incredibly liberating. But am I qualified to faithfully question with compassion? Flood points to Paul's letter to the Corinthians to find the affirmative answer.

How then should we engage these texts? Flood writes,

What about Psalm 137, where the poet asks God's blessing on those who smash the skulls of Babylonian blessings, see my post here, or 139, where the poet hates those who hate the Lord? Shall we remove them from our reading? Shall we go liberal and excise them? No, to remove them is to deny the humanity of the authors and our humanity as readers. Flood writes,

Well said Mr. Flood.

Chapter 5 is titled, "Facing our darkness." Based on his previous chapter, in which he discusses ethics as necessary for Biblical exegesis, he supplements the earlier idea of faithful questioning: faithful questioning motivated by compassion. p. 91 More than any of the previous chapters Flood shows multiple examples from within the Old Testament in addition to inter-Testament questioning.

The problem of evil is a topic of dispute between the authors of the Bible. Unfortunately, one has to go to the old King James translation to get a literal translation of the Hebrew word ra'.

Amos 3:6 Shall a trumpet be blown in the city, and the people not be afraid? shall there be evil (ra') in a city, and the Lord hath not done it?

Isaiah 45:7 I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil (ra') : I the Lord do all these things.

1 Kings 22:23 Now therefore, behold, the Lord hath put a lying spirit in the mouth of all these thy prophets, and the Lord hath spoken evil (ra') concerning thee.

The question is, was God really responsible for these evil things, especially if God is perfectly revealed in Jesus? The Old Testament is full of ascriptions of sickness and defeat to God's judgment. But when Jesus encounters sickness, say a blind man, his disciples want to know whose sin caused it, but Jesus counters neither. Jesus combats sickness and death because they are the work of the demonic, not God. Jesus' move is not unique. Flood notes that a book between the Testaments, Jubilees reframes things attributed to God in the Old Testament and attributes them to the prince of demons. See a short summary of this at Wikipedia. One notorious Bible contradiction serves as an example of Jewish theological development; who motivated David's census. In the earlier account of 2 Samuel 24:1, God did. In the later retelling at 1 Chronicles 21:1, Satan did. Jesus' approach to the world is akin to the later theology of the Chronicler. Evil spirits cause bad things and bad things happen for no reason but God is not the problem but the solution to those bad things.

In the Old Testament, the Babylonian prophet, Ezekiel is a source of a few examples of faithful questioning.

In Deuteronomy 28:63 God is said to be pleased to ruin and destroy his people if they are unfaithful. But Ezekiel 33:11 says God takes no pleasure in the death of the wicked.

In Deut. 5:9 and Exodus 20:5 God punishes the multiple generations for the sin of the fathers, see my post here, but Ezek. 18:19-20 God only punishes the sinner and not the sinner's descendants.

The question is, did God change his mind or did his prophets change their theology in response to faithful questioning with compassion? I used to believe the former, it is simpler when one is committed to an inerrant Bible. As Flood sees it, these contradictions are not mistakes for Bible critics to harp on, but "intentional contradictions, a record of the dispute found throughout the Hebrew canon, cataloging developing and conflicting views of God. Therefore, rather than viewing such contradictions as something embarrassing we need to explain away, we can instead view them positively as a record of moral development that emerges through dispute and protest." p. 98

For me, this is incredibly liberating. But am I qualified to faithfully question with compassion? Flood points to Paul's letter to the Corinthians to find the affirmative answer.

1 Cor. 2:14-17 The person without the Spirit does not accept the things that come from the Spirit of God but considers them foolishness, and cannot understand them because they are discerned only through the Spirit. 15 The person with the Spirit makes judgments about all things, but such a person is not subject to merely human judgments, 16 for, “Who has known the mind of the Lord so as to instruct him?”[Isaiah 40:13] But we have the mind of Christ.Isaiah's question is rhetorical, but Paul does not take it that way. Why not? Because Jesus changes everything.

How then should we engage these texts? Flood writes,

It's also helpful to view these texts from the perspective of the victim, as Jesus so often did. We might, for example, try to read the Exodus story from the perspective of the conquered Canaanites, or view the story of the flood from outside of the ark... we need to ask how Christ and his way of compassion, grace, and enemy love might point to better Jesus-shaped alternatives to the ones found in such passages. p. 105-6.Unintentionally, I have tried this approach myself. One of the leaders in my tribe encourages Bible teachers to look for Jesus in every passage. One time I had to preach on the rape of David's daughter, Tamar, by her half-brother Amnon. As I looked at all the characters in the story, all the men who did nothing to protect her or help her, I looked for Jesus. I found him in Tamar. Innocent, seeking to serve, related, and ultimately violated. I made the risky, for my tribe, proposal that Tamar is the Jesus figure in that story.

What about Psalm 137, where the poet asks God's blessing on those who smash the skulls of Babylonian blessings, see my post here, or 139, where the poet hates those who hate the Lord? Shall we remove them from our reading? Shall we go liberal and excise them? No, to remove them is to deny the humanity of the authors and our humanity as readers. Flood writes,

Just as the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being, it also cuts through the middle of Psalm 139, reflecting our human hearts before God in all of their beauty - and in all of their darkness as well. We can no more cut out these verses than we can cut out a piece or our own hearts. Instead, we need to learn how to honestly face this in the Bible..." p. 112

Well said Mr. Flood.

Comments