ch. 6, a long form book response to Disarming Scripture by Derek Flood

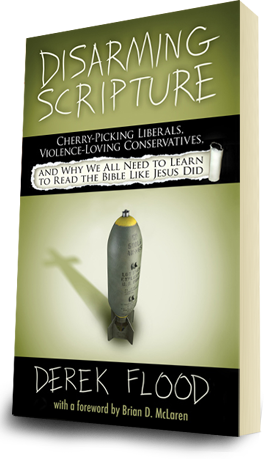

Derek Flood has written an excellent book explaining the issues I covered in my blog series this past autumn. My series is titled "Not everything Biblical is Christian." His book is titled Disarming Scripture. Cherry-picking liberals, violence-loving conservatives, and why we all need to learn to read the Bible like Jesus did. It is certainly a mouthful, but his examples are better than mine and deserve a thorough treatment here. Flood's book is ten chapters long and I intend to speak about each chapter in separate blog posts. I heartily recommend this book for the thinking Christian.

Chapter 6 is titled, "Reading on a trajectory." Flood takes the work of William Webb and takes it past Webb's idea of trajectory in certain areas. This is Flood's proposal, "we cannot stop at the place the New Testament got to, but must recognize where it was headed." p. 124 At first blush this sounds anathema to conservative Christians. But consider slavery as an important test case.

The New Testament certainly sets a trajectory on the topic of slavery by encouraging slaves to seek their freedom, teaching owners to treat slaves as Christ treats them, and teaching the church that in Christ there is no distinction between slaves and free citizens. Despite these doctrines, nowhere in the New Testament is slavery condemned outright. There is no proof text for ending slavery. Hence, many conservative evangelicals around the time of the U.S. Civil War believed they could not condemn slavery as a moral evil because God's Word did not.

Flood includes a paragraph of John Henry Hopkins pamphlet, A Scriptural, Ecclesiastical, and Historical View of Slavery, 1861, but I'll add some more or Hopkins' reasoning.

How is the Christian today to honor God with our "weak and erring" intellects? Flood thinks, since we have the mind of Christ (1 Cor. 2:15), and Jesus says we will know false prophets by the fruits of their teaching (Matt. 7:16), and the fruit of the Spirit of God is love (Gal. 5:22), then we can evaluate the trajectory of New Testament doctrines by their fruit. "If we therefore recognize that a particular interpretation leads to observable harm, this necessarily means that we need to stop and reassess our course. To continue on a course we know to be harmful, simply because 'the Bible says so,' is morally irresponsible." p. 144 The Bible also said touching a dead man makes a Jew unclean, so the priest and the Pharisee pass the robbed and beaten man left for dead on the side of the road. But Jesus praises, in his parable, the Samaritan, considered a heretic by his audience for not worrying about his religious purity. The fruit of the Good Samaritan's doctrine was ripe and the fruit of the doctrine of the "biblical" teachers was rotten.

Slavery is not the hot topic in the church today, LGBTQ human beings are. Before I began faithfully questioning I thought like Bishop Hopkins. Then I came to recognize the harm that position has done and the falsehoods that propped it up. I have changed my doctrine, to the chagrin of a few fellow believers who know my repentance. I still belong to fellowships that complain when mingling between services about all the homosexuality infiltrating TV shows they watch. For now, this is my main venue to advocate in my tribe against their dominant belief that the only homosexual Christian acceptable to God is celibate or married to the opposite sex. I am not capitulating to the culture, but listening to the pleas of gay Christians and acknowledging the rotten fruit of this dominant doctrine.

Chapter 6 is titled, "Reading on a trajectory." Flood takes the work of William Webb and takes it past Webb's idea of trajectory in certain areas. This is Flood's proposal, "we cannot stop at the place the New Testament got to, but must recognize where it was headed." p. 124 At first blush this sounds anathema to conservative Christians. But consider slavery as an important test case.

The New Testament certainly sets a trajectory on the topic of slavery by encouraging slaves to seek their freedom, teaching owners to treat slaves as Christ treats them, and teaching the church that in Christ there is no distinction between slaves and free citizens. Despite these doctrines, nowhere in the New Testament is slavery condemned outright. There is no proof text for ending slavery. Hence, many conservative evangelicals around the time of the U.S. Civil War believed they could not condemn slavery as a moral evil because God's Word did not.

Flood includes a paragraph of John Henry Hopkins pamphlet, A Scriptural, Ecclesiastical, and Historical View of Slavery, 1861, but I'll add some more or Hopkins' reasoning.

Thus understood, I shall not oppose the prevalent idea that slavery is an evil in itself. A physical evil it may be, but this does not satisfy the judgment of its more zealous adversaries, since they contend that it is a moral evil a positive sin to hold a human being in bondage, under any circumstances whatever, unless as a punishment inflicted on crimes, for the safety of the community.

Here, therefore, lies the true aspect of the controversy, and it is evident that it can only be settled by the Bible. For every Christian is bound to assent to the rule of the inspired Apostle, that "sin is the transgression of the law," namely, the law laid down in the Scriptures by the authority of God the supreme "Lawgiver, who is able to save and to destroy." From his Word there can be no appeal. No rebellion can be so atrocious in his sight as that which dares to rise against his government. No blasphemy can be more unpardonable than that which imputes sin or moral evil to the decrees of the eternal Judge, who is alone perfect in wisdom, in knowledge, and in love.

With entire correctness, therefore, your letter refers the question to the only infallible criterion the Word of God. If it were a matter to be determined by my personal sympathies, tastes, or feelings, I should be as ready as any man to condemn the institution of slavery; for all my prejudices of education, habit, and social position stand entirely opposed to it. But as a Christian, I am solemnly warned not to be "wise in my own conceit," and not to "lean to my own understanding." As a Christian, I am compelled to submit my weak and erring intellect to the authority of the Almighty. For then only can I be safe in my conclusions, when I know that they are in accordance with the will of Him, before whose tribunal I must render a strict account in the last great day.Bishop was the Episcopal Bishop of Vermont. His reasoning is normal for fundamentalists and conservative evangelicals today. I have written from this very same position myself on a variety of secondary topics. Yet why aren't these people still railing on Fox news against the government for suspending of the religious rights of those Christians who want to own slaves? (Although there are still Christians today, such as Douglas Wilson, who write books arguing that Southern slave masters were kind hearted Christians and there were only a few bad apples who raped their slaves or beat them to death.)

How is the Christian today to honor God with our "weak and erring" intellects? Flood thinks, since we have the mind of Christ (1 Cor. 2:15), and Jesus says we will know false prophets by the fruits of their teaching (Matt. 7:16), and the fruit of the Spirit of God is love (Gal. 5:22), then we can evaluate the trajectory of New Testament doctrines by their fruit. "If we therefore recognize that a particular interpretation leads to observable harm, this necessarily means that we need to stop and reassess our course. To continue on a course we know to be harmful, simply because 'the Bible says so,' is morally irresponsible." p. 144 The Bible also said touching a dead man makes a Jew unclean, so the priest and the Pharisee pass the robbed and beaten man left for dead on the side of the road. But Jesus praises, in his parable, the Samaritan, considered a heretic by his audience for not worrying about his religious purity. The fruit of the Good Samaritan's doctrine was ripe and the fruit of the doctrine of the "biblical" teachers was rotten.

Slavery is not the hot topic in the church today, LGBTQ human beings are. Before I began faithfully questioning I thought like Bishop Hopkins. Then I came to recognize the harm that position has done and the falsehoods that propped it up. I have changed my doctrine, to the chagrin of a few fellow believers who know my repentance. I still belong to fellowships that complain when mingling between services about all the homosexuality infiltrating TV shows they watch. For now, this is my main venue to advocate in my tribe against their dominant belief that the only homosexual Christian acceptable to God is celibate or married to the opposite sex. I am not capitulating to the culture, but listening to the pleas of gay Christians and acknowledging the rotten fruit of this dominant doctrine.

Comments